Seminar on

The Fiftieth Anniversary of the African Independences

Marginalized, Forgotten, and Revived Political Actors

Organised by IFRA French Institute for Research in Africa

BIEA British Institute in East Africa

23rd and 24th September at IFRA Nairobi

Tanzania: A Nation without Heroes

Speaker

Mohamed Said

TANZANIA - A COUNTRY WITHOUT HEROES

By Mohamed Said

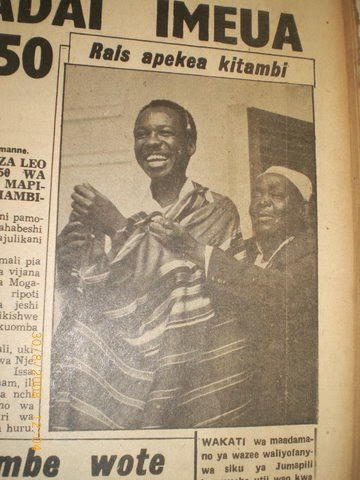

Mzee Mshume Kiyate and Julius Nyerere February 1964.

Nyerere: A Lone Hero of the Struggle for Tanganyika’s Independence

The heading of the paper is from words which the late Hamza Aziztold me during discussion about the political history of Tanganyika. Hamza Aziz was a police officer in the colonial force and one of the TANU informants during the struggle for Tanganyika’s independence in 1950s passing on information to TANU top leadership as to what the police was plotting against the party. After independence Hamza Aziz was made Inspector General of Police (IGP) by Nyerere. Reflecting on what was the end of his elder brother, [1] the once rich and flamboyant Dossa Aziz and his contribution to the struggle for independence, first as a party financier and second as Nyerere’s close friend, ally and right hand man and retrospectively coming to the painful reality that his brother died a poor man; and the fact that his brother does not feature anywhere in Nyerere’s life or in the history of the struggle or in TANU’s history, the party which he was among the 17 founder members in 1954, he sadly uttered these words, ‘’Tanzania is a country without heroes. Tanzania has one hero only and that hero is Julius Kambarage Nyerere.’’

Hamza Aziz’s sadness could probably among other things be deduced from the fact that a street near Mbaruku Street where Dossa had lived during the struggle was at that time recently named after a non entity controversial Muslim politician Yusuf Makamba who together with a Catholic priest Camillus Luambano were a source of Muslim killings in the infamous Mwembechai Mosque raid by the paramilitary in 1998.[2] It was not possible to understand what compelled the city authorities to honour Yusuf Makamba or what criteria was applied to immortalise the man who majority of Muslims consider has Muslim blood in his hands and forget to honour Dossa Aziz after what he did to the country and to Nyerere. Dossa’s house was among two centres where the young nationalists used to meet to organise and strategise against the British. The other place was at Abdulwahid Sykes’s house at Aggrey Street. These two houses should have been preserved and made national monuments for posterity.

Little did Hamza Aziz realise at that time that he was by that sentence reviving sad memories of all forgotten political actors of the post World War II era in Tanganyika. Dossa Aziz died a poor man at Mlandizi a remote village outside Dar es Salaam. There were no eulogies from the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) at his grave side or obituaries in the party newspapers. Nyerere his ‘’comrade in arms’’ during the struggle did not even attend his funeral. Dossa Aziz in his heydays was nicknamed ‘’The Bank’’ because of his wealth and generosity. He had at that time inherited his father’s construction business when his father Aziz Ali died in 1951.[3] Dossa Aziz bankrolled TAA and later TANU and Nyerere with ease until independence was achieved. Dossa Aziz donated a car to the movement for Nyerere’s personal use. This was the first mode of transport to be owned by TANU. No one knows the whereabouts of this vehicle which should have today been preserved and displayed at the National Museum for all future generations.

On hindsight Hamza Aziz was a hero himself though his contribution to the struggle for independence has to date not been requited. Indeed all books written by local and foreign historians on political history of Tanganyika has focused on Nyerere alone completely eclipsing other patriots who equally played important roles in the struggle for independence. [4] Ali Juma Ponda Hassan Suleiman[5] and Ali Migeyo began to organise the people in 1940s immediately after World War II through the African Association (AA) founded in 1929 by Kleist Sykes [6] as founding secretary. Kleist Sykes died in 1949 and he left behind a vast amount of personal papers and diaries which were consulted for the first time by John Iliffe in 1960s while researching the history of African Association.[7]Unfortunately for certain reasons these documents have not been made available to any researcher ever since save for the period when the papers were consulted in the writing of Abdulwahid Sykes’s biography in 1980s.[8] Sykes’s papers make very interesting reading to any student of Tanganyika’s political history. Information in the papers contradicts the known political history of colonial Tanganyika. Interesting is the fact that when Kivukoni Ideological College was researching into the history of TANU the panel of party researchers were notified about the existence of these papers. The panel refused outright to consult these documents satisfying themselves to focus on Nyerere alone. We will in the course of discussion see what the reaction of CCM was when a corrective history of TANU and Nyerere’s own history was attempted by independent researchers. This collection of Sykes papers should have been preserved at the Tanzania National Archives (TNA). These papers should not be allowed to be in private hands

.

.

Karume, ASP, Umma Party: The Zanzibar Revolution Strategists Who Never Were

The political history of Zanzibar is wrought with many events, themes and theories. Popular among Zanzibar revolutionaries are what they refer as the Arab slavery and this is taken as the source of the Zanzibar revolution of January 1964. This is the official history which is taught in schools for half a century and this history has its own ‘’official heroes,’’ which are the Afro Shirazi Party (ASP) of Abeid Amani Karume and Umma Party of Mohamed Abdulrahman Babu and the faction of ‘’comrades’’ who claim to have planned, organised and rose up in arms to overthrow the Arab oligarchy. The foundation of party politics and democracy built by Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) popularly known as Hizbu is hardly mentioned. Again surprisingly little is known of the army of Makonde tribesmen forming a mercenary force from sisal estates in Sakura and Kipumbwi from Tanga in Tanganyika who were smuggled into the isles armed with machetes to beef up ASP. The Makonde fought in the night of the revolution and the day after killing many so called Arabs who they perceived had enslaved Africans for almost three centuries.

Nowhere is this army of mercenaries mentioned in the history of the Zanzibar Revolution or the people who planned, financed and organised the Zanzibar invasion (to borrow Ali Muhisin’s and Sultan Jamshid’s analogy) from Tanganyika. Fifty years after the revolution members of the ASP deny participation of any force from Tanganyika in the Zanzibar revolution. Surprisingly those who claim to have laid the foundation of the revolution have not documented their participation on how they participated in the revolution. The official hero of the Zanzibar Revolution is Karume though he was in the dark about the plot and came to know of the conspiracy to overthrow the government at the eleventh hour. But the most puzzling piece of jigsaw is John Okello who was seemingly the hero of the revolution. It was his voice which announced the fall of the Zanzibar government. Okello was neither at Sakura nor in the corridors of ASP nor is there any evidence that before the day of the revolution this man was known in the politics of Zanzibar.

The name of Julius Nyerere, Kassim Hanga and Oscar Kambona who were the mainstay of the plot do not appear anywhere in the history of the revolution nor the names of Victor Mkello and Mohamed Omari Mkwawa the two who with the connivance of the state machinery in Tanganyika recruited the Makondes from the sisal estates in Sakura to participate in the 1963 Zanzibar elections voting for ASP and to overthrow the government in 1964.[9] However these Makondes today remain faceless and nameless after years of denial and suppression of their role in the revolution. Where are the Okello tapes? Are they not part of Zanzibar history? Should they not be played and listened to by the people during anniversary of the revolution? Or are the tapes and Okello’s role in the revolution an embarrassment today? Can a nation deny its own existence and therefore its own history?

The names of Jumanne Abdallah and Ali Mwinyi Tambwe, the two top government leadership in Tanga region involved in laying the groundwork for the invasion from Kipumbwi are nowhere to be seen in the saga. Throughout his entire life Ali Mwinyi Tambwe refused to talk about his role in the Zanzibar Revolution. But the jewel in the crown is the omission of Algerians and Israelis in the history of the Zanzibar Revolution much as a lot has been written on the role of United States government and Britain. Ben Bella the president of Algeria provided guns which were received in Dar es Salaam and Israeli it is believed played a subtle role through Moshe Finsilber though it is not clear what Moshe actually did. [10] Further research is to be done to uncover the actual role of Moshe Finsilber in the Zanzibar Revolution. No wonder many political actors are missing in the dramatis personae of the Zanzibar Revolution play.[11] The history of atrocities which were carried out by Zanzibar Revolutionary Council and the ‘’Committee of Fourteen’’ led by the notorious Seif Bakari and his followers is another area yet to be researched.[12]

This notwithstanding there has been attempts by individuals to uncover what happened during the dark days in Zanzibar particularly from 1964 to 1972. Among those who attempted to uncover the truth Ali Nabwa’s name stands out as a lone voice. Jim Bailey the proprietor of the Drum magazine was the first person to come across Ali Nabwa’s ‘’Prison Letters,’’ the letters which were seen for the first time by the present author in 1994 of which years later he had this to write in an obituary following Ali Nabwa’s death in 2007:

It was through this manuscript[13]that I came for the first time face to face with Nabwa’s pen through his Prison Letters. The letters introduced Nabwa’s mind to me in a way that I cannot find words to describe. In those letters Nabwa’s pen was not writing but weeping and whipping. The words from Nabwa’s pen were taking me to a different world which even in my wildest imagination I never thought existed. The first letter written in 1973 from Central Police Station Dar es Salaam shocked me. In that letter Nabwa described intimidation and torture by the police in the style replica of the Ton Ton Macouts of Papa Doc’s Haiti. In Nabwa’s sense of humour in the letter he says it needs a Dickens to describe the squalor of the cell he was in. The letters which followed were all from Condemned Section of Ukonga Prison. In his analysis of the personalities which people were made to believe were symbols of justice and principles Nabwa’s pen removed the charade and the camouflage to reveal their true colours and identity. Nabwa’s letters were a potpourri of short biographies, dossiers, profiles, hit list of ‘enemies’ and method of their execution. In the Prison Letters Nabwa’s pen exposed the atrocities which took place in Zanzibar after the revolution and analysed the arrogance, mediocrity and sheer myopia of the leadership. Now looking back I am happy that I was among those privileged to read Nabwa’s revelations of injustices in Zanzibar before he became a celebrity of sorts and his revealing articles major topic of discussion in the corridors of power.

The atrocities which no one had the courage to speak about them publicly for almost forty years were laid bare for all to read through Dira the paper which Nabwa founded in 2004. Dira was the first free newspaper in Zanzibar since the revolution. The ripples from Nabwa’s pen were electrifying. Dira became a paper eagerly awaited by the public including Zanzibar leadership each week. Its circulation rose each passing week. Nabwa’s pen was lifting the lid in broad daylight. The stories of treachery, rape, murder, homosexuality, forced marriages by members of the Revolutionary Council and their cronies in Zanzibar were all there with names, places and accomplices for all to read and pass judgement. Those who had demonised the Sultan had no tongue to defend their own ‘upright’ track record. The young generation began to ask questions and in the answers they saw the leadership in power and the revolution in a different light all together.

On the contrary the sultan left Zanzibar his hands untainted with blood. This cannot be said to the government which came into power after the revolution.[14] Adam Shafi himself a victim of those atrocities has vividly portrayed the times in his novel ‘’Haini,’’[15] thinly and unconvincingly disguising his narration as fiction.

The political history of Tanganyika and Zanzibar remains undocumented to date, save for the efforts by Ghassany and the author of this paper to present respectively a contrary view of the official history. [16] The official version has conveniently omitted the decisive role of many patriots. The corrective version has attempted to insert back into history those forgotten patriots including the unpalatable realities and hard facts. Yash Tandon has lamented on the neglect of patriots who fought for independence of their countries. Tandon called the forgotten heroes like Abdulwahid Sykes and other patriots like Chege Kibachia, Makhan Singh, Fred Kubai, James Kivu, I.K. Musazi, Erika Fiah and Gama Pinto as ‘’veteran leaders of the struggle of the peoples of East Africa... whom our recent historians have forgotten.’’[17]

In Tanzania the book, ‘’The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes (1924 – 1968) the Untold Story of the Muslim Struggle against British Colonialism,’’[18]has completely changed the history of Tanganyika’s struggle for independence. The work has brought into the fore patriots who were in the struggle many years before Nyerere. But the shocking revelation in the book was the fact that TANU was the brainchild of Abdulwahid Sykes and not Nyerere and that its origin emanates from Kleist Sykes, Abdulwahid’s father who founded the African Association in 1929 and Al Jamiatul Islamiyya fi Tanganyika (Muslim Association of Tanganyika) in 1933 the two associations which later in 1950s provided leadership to TANU. Unique in these two associations is the fact that for many years the office bearers were the same.

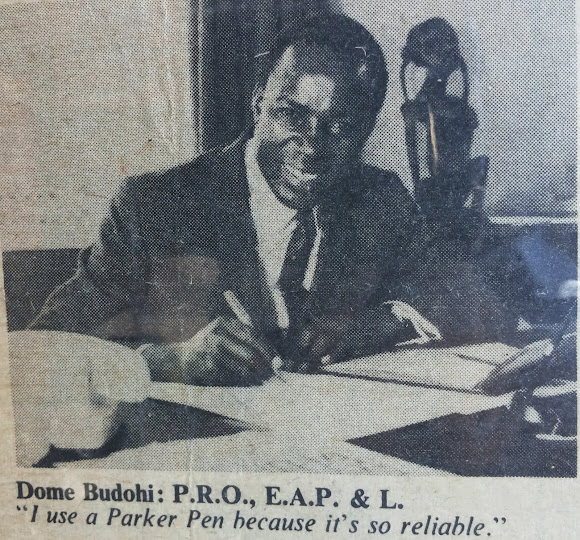

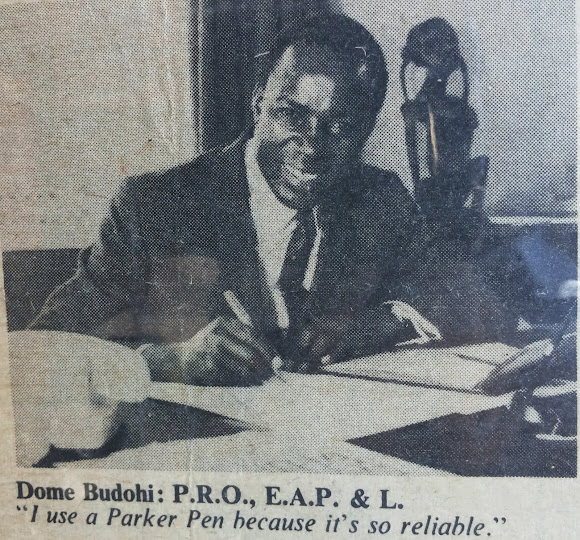

Having purposely buried those who fought for independence consequently part of the history of these countries is lost. Students of political history in East African countries are in the dark about important events which took place and carried out by the forgotten patriots. For example few are aware that there was an attempt in 1950 by Kenya African Union (KAU) and TAA through their leaders, Kenyattaand Abdulwahid to link the Kenyan struggle during Mau Mau with that in Tanganyika and a secret meeting was held in Nairobi between the two. During the Meru Land case in 1950 Tanganyika sought help from Kenya to assist them in confronting the settler community in Meru.[19]There were also Kenyans in TAA Executive Committee prominent among them were Dome Okochi Budohi, Patrick Aoko and C Ongalo. These three Kenyans in the TAA executive committee held office alongside Abdulwahid Sykes and Nyerereand were among the early members of the African National Union (TANU) when the party was formed in 1954.[20]

This piece of information here below stands as witness to the rich history which for many years remained unknown:

Abdulwahid and his friend Ahmed Rashad Ali went to a house in the suburbs which was in darkness and surrounded by Mau Mau guards. He was expected. Kenyatta was informed and came out of the house to receive him. This meeting took place under the cover of darkness probably in Eastleigh in the suburbs of Nairobi where most of the 1950s Mau Mau meetings before the emergency took place. Ahmed Rashad Ali recalls that he heard Kenyatta calling Abdulwahid by name. Kenyatta had known Ally Sykes in Nairobi in 1946 and it is most probable that Abdulwahid’s work was made easy by that acquaintance. Ahmed Rashad Ali met Kenyatta and they shook hands. After introductions, Kenyatta, Abdulwahid, Fred Kubai, Bildad Kaggia and Kungu Karumba went to another room where the meeting took place. Ahmed Rashad remained outside with a guard.[21]

Another meeting was proposed by Kenyatta to be held in Arusha and TAA was to be presented by Abdulwahid Sykes, Steven Mhando and Dossa Aziz. This meeting never took place because ‘’Operation Anvil’’ came into operation soon after.

In 1955 Dome Budohi and Patrick Aoko and other Kenyans were among Kenyans rounded up in Dar es Salaam following ‘’Operation Anvil’’ which came into operation in Kenya in 1954. Budohi and Aoko the two active Kenyans in TANU were remanded at Central Police Station[22] in Dar es Salaam and were all the time kept in chains. Budohi was the first Kenyan to join TANU and was the proud bearer of TANU card no. 6.[23] Budohi and Aoko were interrogated for six months and then sent to a camp in Handeni to be transported to detention camps in Kenya. Budohi was detained in Lamu Island. The Kenyan nationalists were packed in cattle wagons chained and they passed through Korogwe and Taveta on their way back to Kenya. Ally Sykes then transferred to Korogwe as punishment for being among the 17 founders of TANU went to the railway station to see them off.

Among the staff working at the Handeni camp was Rashid Mfaume Kawawa later to be Vice President of Tanganyika. In Kawawa’s biography [24]his stint at the camp in Handeni is not mentioned. Kawawa’s book has nothing on these Kenyan patriots who struggled for Tanganyika’s independence and about his experience with them at the Handeni Mau Mau camp and what became of them when both Kenya and Tanganyika gained independence. Nyerere has never talked about these Kenya nationalists either. Budohi and Kawawa were both entertainers of their time, the cool, elegant young men of Dar es Salaam of 1950s. Budohi was a talented musician playing with the Skylarks Band with the Sykes brothers and Kawawa was an actor.

How is this so? Budohi and Kawawa knew each other very well. The two had acted together in a movie “Wageni Wema” made by Community Development Department let alone that both were budding young politicians. Kawawa surely must be having a lot of fond memories of those days long gone. It is also strange that Kawawa’s book does not have references to his personal papers which are not only important to Kawawa’s life history but to the history of Tanganyika as well. Kawawa’s book does not mention contemporaries and fellow trade unionists of his time in Tanganyika African Government Servants Association (TAGSA) like Ally Sykes, Dr. Wilbard Mwanjisi, Thomas Marealle and others. Why this was not in his book one can only speculate. It is now known without any shade of doubt that such kind of information was surpassed because it was not to the interest of those in power it is known that there were efforts to liberate the country before their time. Kawawa’s book which should have been a political biography remains drab all the way through the pages.[25]

The Forgotten Patriots, Heroes and Heroines

The struggle against British colonialism in Tanganyika was fought by many and from every angle. There were the known front liners, patriots of the TAA like Abdulwahid Sykes and his young brother Ally, Dossa Aziz, John Rupia,[26] Steven Mhando, Dr. Vedasto Kyaruzi, Hamza Mwapachu (1913 – 1962)[27], Idd Faiz Mafongo,[28]Mshume Kiyate,[29]Joseph Kasella Bantu,[30]and Zuberi Mtemvu in Dar es Salaam, Ally Migeyo,[31]Saadan Abdu Kandoro and Paul Bomani from the Lake Region, Yusuf ‘’Ngozi’’ Olotu [32]from Kilimanjaro, Bilali Rehani Waikela,[33]Germano Pacha, Fundi Muhindi from Tabora, Yusuf Chembera and Salum Mpunga from Lindi, Hamisi Heri, Sheikh Rashid Sembe,[34]Mohamed Kajembe from Tanga… the list is long. There were also the not so well known like Lameck Bogohe who is also in the list of founding members of TANU. [35]

In this category there were the Swahili women groups and societies who turned ‘’lelemama’’ songs into songs of protests and revolution. Famous among them was Bibi Titi Mohamed (1926 – 2007),[36] Hawa Bint Maftah, Tatu Bint Mzee of Dar es Salaam, Shariffa Bint Mzee of Lindi, Halima Selengia[37] of Moshi, Dharura Bint Abdulrahman of Tabora, Mwanamwema bint Sultan of Tanga and many others pushing their struggle against colonialism through Muslim women societies and ‘’taarab’’ groups like ‘’Bomba Kusema,’’ ‘’Egyptian,’’ ‘’Al Watan,’’ ‘’Saniyyat Hubb,’’ ‘’Arab Congo’’ etc. etc. But the bed rock of the struggle was the Muslim clergy, the sheikhs like Sheikh Mohamed Ramia of Bagamoyo, Sheikh Yusuf Badi of Lindi and Sheikh Rashid Sembe of Tanga and ‘’maalims’’ of ‘’madrasas’’ and the ‘’tariqas’’ with the ‘’murids’’ who provided membership and leadership to TANU branches all over Tanganyika. The leader of this movement was Sheikh Hassan bin Amir[38] who was the Mufti of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. All these patriots mentioned above although in passing were heroes in their own particular ways. Unfortunately all of them are missing in Tanganyika’s political history. One may ask, ‘’Where was the Church, what role did the Church and the Christian clergy play during the struggle?’’ This is the bone of contention in the history of the struggle for independence in Tanganyika. The official version has conveniently omitted the decisive role of Muslims and Islam as an ideology of colonial resistance against foreign domination in Tanganyika. In Tanzania it is a taboo to associate the struggle for independence with Islam and Muslims. Is it because in Tanganyika the Church never played a significant role in the struggle for independence? It is also a fact that Christians assumed leadership positions in the independence government and are still monopolising those positions because of their superior education. Can this be the reason why Muslim contribution to independence struggle has over the years been down played? [39] It is said those close to Nyerere urged him to write about the struggle for independence but he always refused. Oxford University Press who published many of his books even sent an emissary to him to discuss the subject but he turned them down. Could the fear of Muslims been the reason for his refusal? The Fear of History and Heroes Leaders in Africa seem to fear heroes other than themselves. If Bildad Kaggia had not written his autobiography ‘’Roots of Freedom’’[40] the history of Mau Mau in Kenya as a peasant movement against British colonialism would have many gaps. In absence of that work and many others by other patriots it would not have been possible to link the Kenyan struggle with the names of patriots like Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Pio Gama Pinto, Makhan Singh and Dedan Kimathi. Much as it is difficult to divorce the Kikuyu and Mau Mau from the struggle in Kenya so it is impossible to divorce the role of Muslims in spearheading the struggle against the British and in founding of TANU the party of independence. The Kikuyu bore the brunt of colonialism more than any other ethnic group in Kenya the way Muslims suffered more than any other group in colonial Tanganyika. In Kenya the British in their tactics of ‘’divide and rule’’ the focus was on ethnicity divide. The British appropriated Kikuyu land thus turning Kikuyus into squatters in their own land. As a result of this land grabbing policy of the British settler community the Kikuyu rose to the occasion and engaged the British through Mau Mau. In Tanganyika because of absence of tribalism the British fell back on religion to divide the people. Christians were elevated at the expense of Muslims. Christians through missionary schools and government grants were provided with schools to educate their children while Muslims were left to fend for themselves. Muslims suffered as colonised subjects singled out for discrimination by being denied education, curtailing any chances for self-advancement. The survival of Muslims as a people and Islam as a religion therefore lay in the total overthrow of the colonial state. A nation which is formed from such a historical background of factions as in Tanganyika and Kenya of which those divisions were made by the colonising power with the sole purpose of creating rifts among the people is without any shade of doubt is going to create problems for any emerging African nation. First is the fact that during the struggle for independence there would be certain factions in the body politic whose support to the struggle would be lukewarm. There would also be factions who would prefer to sit on the fence as dependable mechanism to safeguard their privileges under colonial setting. This is because these factions feel colonialism is of benefit to them due to the privileges extended to them by the colonial government. But these positions are not tenable in a free country. In post colonial environment all factions including those who sat on the fence would wish to share power irrespective of their position to the struggle. These factions will no longer be satisfied with crumbs. They will demand the main course of the menu in capacity building and state formation. The direction of the country and indeed interpretation of peoples’ history will therefore depend on who takes the reins of power. If it is the comprador class which assume power after independence the country will find itself in a situation which faced and is facing many African countries today. The trend has been for that class in power to strive to find enemies among those who fought for freedom in order to justify and maintain their positions in society. The heroes who fought for independence are by stroke of a pen turned to enemies of the state. Fallacies, Half Truths and Omissions The political history of Tanzania is a victim of official history and witch hunting which followed immediately after independence. Official histories which are a norm in many authoritarian regimes choose and pick what it considers as appropriate to be included in the history of a nation. ’The ‘’truth’’ according to official histories usually goes contrary to facts. For many years people were made to believe that the urge for the people of Tanganyika to have a political party to fight for independence began with Julius Nyerere in 1954. This is a fallacy. The urge for the people of Tanganyika to organise themselves began in 1929 with the formation of the African Association (AA) in Dar es Salaam. The trend in Tanzania has been to down play the quarter century history of African Association and its leadership. The achievements of the African Association remained undocumented and very little were known about its leadership.[41] In 1986 after a silence of almost 25 years Ally Sykes (1926 – 2013) one of the 17 founder members of TANU in 1954 and a person who holds TANU card no. 2 and the person who issued card no. 1 to Nyerere the card which bears his signature gave an interview to a British journalist Paula Park. Park wrote a full page article on the Sykes’s family contribution to the political development of Tanganyika culminating into the founding of TANU in 1954.[42] Shortly after, Park was paid a visit by immigration officials and quietly asked to leave the country. In 1988 an article was published in African Events (March/April) 1988 (pp 37- 41) in which Abdulwahid Sykes and other forgotten TANU pioneers received prominence. It is the norm that anything contrary to the official history is met with threats, hostility and at times sheer contempt. The author received sharp rebuke from Party historian, Dr. Mayanja Kiwanuka, a leading member of the panel which wrote Historia ya Chama Cha TANU 1954-1977, the official history of TANU and that particular issue was quietly removed from circulation.[43] The article could not be allowed to be read because it contradicted the official TANU history. In 1951 Abdulwahid and Ally Sykes, Mwapachu Dr Joseph Mutahangarwa, Chief Abdieli Shangali of Machame, Paramount Chief Thomas Marealle of Marangu, Chief Adam Sapi Mkwawa, Chief Harun Msabila Lugusha, Dr Mwanjisi, Abdulkarim Karimjee, Dr Vedas Kyaruzi, Juma Mwindadi, H.K. Viran, Stephen Mhando and Dossa Aziz.were requested by Ivor Bayldon, [44] Brig. Scupham and V.M. Nazerali [45] to support formation of a multiracial political party. A glaring omission from this list is the name of Julius Nyerere. Bayldon, Scuphum and Nazerali were members of the Legislative Council. African members of the Legislative Council who were enthusiastic about this new development of interracial alliance in politics were Chief Kidaha Makwaia and Yustino Mponda of Newala. Abdulwahid and the TAA inner circle refused to support this idea because TANU existed in their minds. Abdulwahid Sykes had for many years been trying in vain to convince the powerful Chief David Kidaha Makwaia of Shinyanga to join TAA and be elected president and thereafter to form TANU. Chief Kidaha had made a mark in the politics of colonial Tanganyika in the Legislative Council. It was obvious to many that Chief Kidaha would lead the country as its first Prime Minister in free Tanganyika. Unfortunately to Chief Kidaha while he was seemingly ready to lead Africans of Tanganyika but he thought that leadership should come to him through a political process initiated by the British and not through the political movement by the TAA under the leadership of ‘’agitators’’ like Abdulwahid Sykes, Hamza Mwapachu and Sheikh Hassan bin Amir the members of TAA Political Subcommittee. [46] Chief Kidaha politely declined the offer. In 1953 when Abdulwahid gave this offer to Nyerere he accepted, was elected TAA president in June 1953 [47] and soon TANU was formed in July 1954. Despite of this Abdulwahid and Ally Sykes including their father Kleist Sykes and other patriots are not mentioned in the history of TANU.[48] It is not possible for any researcher to trace the origin of TANU outside the circle of the Sykes family. When Abdulwahid Sykes died in 1968 Brendon Grimshaw then Editor of Tanganyika Standard wrote an obituary in which he paid a glowing tribute to the Sykes family on its contribution to the political development of Tanganyika and without mincing words and without fear stated that ‘’much of the desire among Africans for a powerful political party in Tanzania came from the drive of the Sykes family.’’ [49] Any attempt to rewrite TANU history by focusing on Nyerere and marginalising other patriots is bound to be met with many obstacles. Chief Kidaha and Abdulwahid Sykes are hardly mentioned in the history of TANU. Was Nyerere aware of what had transpired between Abdulwahid Sykes and Chief Kidaha before he appeared on the scene? As fate would have it soon after independence Nyerere abolished chiefdoms and soon thereafter Chief Kidaha was arrested and ostracised to Tunduru a remote area in southern Tanganyika. Did Chief Kidaha get the time to reflect on his misjudgement decision to shun TAA and Abdulwahid’ offer? When he was released from detention Chief Kidaha immigrated to Kenya. Chief Kidaha’s history and contribution to political development in Tanganyika while serving as member of the Legislative Council in 1950s is not known to many students of Tanganyika’s history. It is a pity that Chief Kidaha never talked publicly about his political life and why he fell out with Nyerere. Chief Kidaha’s obituary had this to say about his stand in African politics of 1950s: ‘’Aware of the white man's ambitions for him, the canny chief avoided contact with "Young Turks" in the nationalist movements springing up at the time.’’ [50] It is easy now to be able to understand the stand taken by Chief Kidaha at that time through publication of new information on decolonisation of Tanganyika. There is now new information that beginning 1950 the Special Branch embarked on a systematic campaign of surveillance on the TAA leadership and the names of Abdulwahid Sykes (who the reports contemptuously referred to as a Zulu), Steven Mhando and Hamza Mwapachu [51] (who the government labelled as ‘’communists’’) and Mashado Plantan editor of Zuhra were high on Special Branch list. Chief Kidaha could not have been unaware of this because of his proximity to Governor Edward Twining and the colonial government. [52] Historians in Tanzania have ignored Chief Kidaha Makwaia as they have ignored Abdulwahid Sykes. This is the reason why the genesis of mass mobilisation and the founding of TANU have skipped the two including others who were in the TAA Political Subcommittee and the focus has always been on Nyerere and Nyerere alone forgetting the fact that Nyerere came into lime light in 1953 when he defeated incumbent Abdulwahid Sykes for presidency of TAA. And again it is strange that when it is required to mention that Nyerere took leadership of TAA in 1953 the names of TAA leaders are as a rule not mentioned. The Propagandists, the Singers and the Songs for Freedom Radio broadcasting was introduced in Tanganyika in 1952. The colonial government set a up a radio station ‘’Sauti ya Dar es Salaam’’ which later came to be known as Tanganyika Broadcasting Corporation (TBC). The radio was mainly used by the colonial government for its own purpose of disseminating information that was relevant to its own administrative policies and propaganda. In between these tasks the government played music for entertainment of Africans and its colonial staff. This transformation introduced into the country a variety of music and artists from outside Tanganyika. The recording company His Masters Voice (HMV) which had Red Label for music from Europe introduced the Blue Label which was set aside for recording ‘’natives.’’ This encouraged local artists to compose and record their music which found their way to local air waves. Overtime African music gradually changed its tempo from love songs to songs of protests. These songs went hand in hand with the waves of agitating for freedom and the lyrics conveyed special message to the people. For obvious reasons these songs could not be recorded and therefore be played by the local radio station. But somehow a few of them found their way into the studios of record companies in Kenya and Johannesburg.[53] Among the artists who sang for freedom and were able to record songs of protest were Frank Yosef Humplink (1927 – 2007)[54] and Salum Abdallah. The song ‘Yes No’ by Frank Humplink was the signature tune for TANU and was played before meetings to warm the stage before Sheikh Suleiman Takadir introduced Nyerere to address the people. The lyrics of the song ‘’Yes No’’ was perceived by the colonial administration in Tanganyika and Kenya as smacking of agitation against foreign domination and therefore inciting people to rebel. At that time Mau Mau was raging in Kenya, in Uganda Kabaka was in exile in Britain and there was war in Korea. In this kind of political climate the words in the song in which Frank Humplick mentioned China, Korea, Nyasaland and Communism the song it seems conveyed a special message to the oppressed. Overnight this song became a protest song for nationalists. The song became very popular and was sung by people everywhere. In no time Special Branch got wind of the message of the song and it did not seem to like the lyrics. The colonial administration became worried with the song particularly the mention of communism, China and the reference to British colonies in East Africa which were anyway already in turmoil particularly the Mau Mau uprising in Kikuyu led by Dedan Kimathi not to mention the agitation by Hastings Banda in Nyasaland. The government banned the song and Frank Humplink was arrested. Special Branch was assigned to make sure that all copies of the song were destroyed. A house to house ‘’search and destroy’’ operation was conducted by the police and ‘’Sauti ya Dar es Salaam’’ stopped to play the song which for obvious reasons was very much in demand by listeners. Frank Humplick received unexpected publicity and went down in history of Tanganyika to be the first artist whose work was banned by the government.[55] Salum Abdallah’s song ‘’Kuku Mweusi Anapigana na Kuku Mweupe’’ with lyrics depicting the friction between races in colonial setting passed unnoticed and it enjoyed the air waves unmolested. Salum Abdallah after independence and before his death in 1965 was to compose songs praising Nyerere with messages of mobilising the people for nation building. Not a statue or a anything to remember this great band leader can be seen in his home town Morogoro where in 1947 he had set up his famous band – Cuban Marimba Chacha Band. But veterans of the struggle whenever they hear his music those tunes take them back through memory lane to the days of the struggle and to the early years of independence. There were also the propagandists who overtly and covertly spread the word both in print and in songs against the government like the Bantu group and its prominent members Athmani Issa who was the chairman and Hamisi Barika secretary, other prominent members were Rashid Sisso[56] and Juma ‘’Mlevi,’’ Suleiman. Bantu group was the responsible for providing security to Nyerere. Among these patriots was Ramadhani Mashado Plantan the editor and proprietor of Zuhra the unofficial mouth piece of the TANU and Nyerere.[57] Frank Humplink and Salum Abdallah unfortunately are not part of the history of the struggle of the people of Tanganyika against colonialism. Nothing exists in the National Museum about his their lives nor are the discs of the times in exhibition. Conclusion Where have the heroes and heroines of the struggle for independence gone to? Is it that Tanzania is an ungrateful nation and therefore hates its heroes? This is now the bone of contention between Muslims and the government. Muslims without mincing words are now pointing an accusing finger to the Church particularly the Catholic Church which it is believed in connivance with President Nyerere frustrated hopes and aspirations of Muslims in free Tanganyika, a country they liberated from colonialism in 1961.[58] Muslims are now organising nationwide mass rallies which openly and in live broadcasts through Muslim radio stations denounce the church, criticise the government and church agents within the ruling party CCM and the Parliament for oppressing Muslims. Seemingly derogatory words like “pandikizi” (singular) and “mapandikizi” (plural) meaning “turncoats;” or the new coined word “Mfumo Kristo” roughly meaning “Christian dominance” are now part of the Muslim and Swahili vocabulary. These analogies are used freely in the Muslim media and among Muslims in every day conversation. But what usually thrills Muslims and utterly significant showing that times have changed is when in the rallies and in normal discussion Muslims refer to Nyerere hitherto known respectfully as “Baba wa Taifa” as “Baba wa Kanisa,” meaning “Church Elder.” [59] The move by the Catholic Church to make Nyerere a saint has not helped matters. More so it proves all the allegations levelled against him that he never was a nationalist but a Catholic zealot. Respect and love which Muslims once had for Nyerere has been completely wiped out. The new generation of Muslims no longer believe in the official history of TANU and the propaganda that it was Nyerere who single handed defeated the British. Muslims instead are in their own ways honouring the forgotten heroes of independence movement and in so doing invoking emotions particularly in the new generation to stand up against oppression as their forefathers had done against foreign domination. Muslim heroes of the Maji Maji War like Suleiman Mamba, Ali Songea Mbano,[60] and Muslim nationalists like Abdulwahid and Ally Sykes, Dossa Aziz, Sheikh Hassan bin Amir, Sheikh Suleiman Takadir, Sheikh Yusuf Badi, Bibi Titi Mohamed, Bibi Tatu bint Mzee, Bilali Rehani Waikela,[61] Ali Migeyo and others are now part of nationalist history which was suppressed for many years.[62] Muslims are demanding the restoration of their history and honour as true liberators of Tanganyika. This is unprecedented. One can only speculate and wonder where this would lead to. Can we identify this phenomenon as corrective and revision of history or is it a lesson of anarchy in recording history? [63] |

| |

TANU Bantu Group 1955 | |

[1] Dossa and Hamza Aziz were sons of Aziz Ali a building contractor and one of richest Africans in colonial Tanganyika.

[2]For details on the killings see Hamza Mustafa Njozi, Mwembechai Killings and Political Future of Tanzania, Globalink Communications Ottawa, 2000. The book is banned by the government.

[3] Aziz Ali’s death appeared in the Tanganyika Standard newspaper with banner headline, ‘’the builder of mosques is dead’’ for most of the mosques in Dar es Salaam were built by him and supplied the mosques with lanterns for lighting during the days when Dar es Salaam did not have electricity. Aziz Ali maintained the lanterns providing kerosene to them throughout his life.

[4]See Iliffe, John, A Modern History of Tanganyika, Cambridge University Press, London, 1977, Duggan, W R and Civille, J,R Tanzania and Nyerere, Orbis Book, Maryknoll New York, 1976, Chiume, M W K, Vituko Vya Uhuru, Pan-African Publishing Company Ltd, Dar es Salaam 1973, Chuo Cha Kivukoni, Historia ya Chama Cha TANU 1954 – 1977, Dar es Salaam 1981. |

[5] Iliffe (ed) ‘The Politicians Ali Ponda and Hassan Suleiman,’ in Modern Tanzanians, pp.227-253.

[6] See Daisy Sykes Buruku, ‘The Townsman: Kleist Sykes’, in Iliffe (ed) Modern Tanzanians,Nairobi, 1973, pp. 95-114.

[7] John Iliffe, ‘The Role of the African Association in the Formation and Realization of Territorial Consciousness in Tanzania’. Mimeo. University of East Africa Social Sciences Conference, 1968.

[8]The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes (1924 – 1968) the Untold Story of the Muslim Struggle against British Colonialism in Tanganyika, Minerva Press London, 1998.

[9] See Harith Ghassany, Kwaheri Ukoloni Kwaheri Uhuru Zanzibar na Mapinduzi ya Afrabia, 2010.

[10]Moshe Finsilber played host to Moshe Dayan Israel Six Day war hero in 1967 when he visited Zanzibar in 1961 before the June Riots.

[11] Badawy Qullatein a Marxist and trade unionist was among those involved in the revolution. He died in 2011 in Makka during pilgrimage without writing his memoir. Those close to him admit that Qullatein had a lot of information on Zanzibar Revolution. Although he was a leading figure in the Umma Party he was close to members of the ASP - Seif Bakari, Hassan Nassor Moyo, Saleh Saadalla and Abdulaziz Twala. He was the person who immediately after the overthrow of the government sat down with John Okello to form the Revolutionary Council. His personal papers have not been made public and are in the custody of his family in Dar es Salaam. Later in life Badawy the firebrand leftist of the Zanzibar Revolution became a ‘’sufi’’ and spent the rest of his life between his house and Kitumbini and ShadhilyMosques in Dar es Salaaam. When Tanzania passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2002 Badawy was among Muslims rounded up for interrogations by the FBI. Badawy politely told his interrogators that they have come to him very late they should have came ‘’yesterday.’’ He told them that he regrets dearly that he lost an important period of his lifetime in useless pursuit of politics. The FBI had no further questions and allowed him to go home.

[12] There is information that there is in existence in private hands a 10 page document depicting how Abdallah Kassim Hanga was murdered after being transferred from Ukonga Prison in Dar es Salaam to Zanzibar in 1968.

[13]The manuscript ‘’Tanzania: The Story of Julius Nyerere,’’ was personally presented to the author by proprietor of Drum magazine Jim Bailey in Dar es Salaam on 3rd November 1994 for editing. Bailey was introduced to the author by Ally Sykes.

[14]Obituary by M. Said: ‘’The Weeping Whipping Pen of Mohamed Ali Nabwa (1936 – 2007’’ For more information on the changing political climate in Zanzibar see Marie-Aude Fouere, ‘’Reinterpreting revolutionary Zanzibar in the media today: The case of Dira newspaper,’’ in Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2012 pp. 1-18.

[15] Adam Shafi, ‘’Haini’’ Longhorn Publishers Kampala, 2003.

[16]The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes (1924 – 1968) the Untold Story of the Muslim Struggle against British Colonialism in Tanganyika, Minerva Press London, 1998. Also see Harith Ghassany, Kwaheri Ukoloni Kwaheri Uhuru Zanzibar na Mapinduzi ya Afrabia, 2010.

[17] Yash Tandon, ‘In Defence of Democracy’ Inaugural Lecture Series No. 14, Dar es Salaam, 1979, pp. 47-48.

[19]See Iliffe A Modern History of Tanganyika, Cambridge University Press, London 1977 pg. 502 quoting letter by Sykes to Sablak 8 December 1952 Also Japhet Kirilo’s papers TNA.

[21] This information is from Ahmed Rashad Ali broadcaster for Radio Free Africa in Cairo a radio station set up by Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt in 1950s as propaganda machinery for African countries fighting to liberate their countries from colonialism. In that position Ahmed Rashad came to know many freedom fighters including Jomo Kenyatta. For more information on Ahmed Rashad Ali see Maisha na Nyakati za Abdulwahid Sykes (1924 – 1968) Historia Iliyofichwa Kuhusu Harakati za Waislam Dhidi ya Ukoloni wa Waingereza katika Tanganyika, Phoenix Publishers Nairobi 2002 pp 199 – 205. Ahmed Rashad Ali Many years later had an audience with President Kenyatta at the State House in Nairobi. Surprisingly Kenyatta remembered him as the person who accompanied Abdulwahid to that meeting in Nairobi in 1950. The President called his official photographer who took their photograph posing together. This photograph decorated the living room of Ahmed Rashad Ali for many years. President Kenyatta also presented him with a tie with the national colours of Kenya.

[22] This building still stands in its original form although it is not now a police station. A plaque on the building to honour the nationalists who spent time there will help in preserving that history.

[23] Julius Nyerere card no. 1; Ally Sykes card no 2, Abdulwahid Sykes card no 3; Dossa Aziz card No. 4; Denis Phombeah card No. 5; Dome Okochi Budohi card no. 6 John Rupia card No. 7; Bibi Titi Mohamed card No. 16; Idd Tosiri card No. 25.

[24]John M. J. Magotti, “Simba wa Vita Katika Historia ya Tanzania Rashidi Mfaume Kawawa,” Matai and Co. Ltd. 2007.

[25]The present author wrote an article cum book review on the book, ‘’A Tale of Two Books and the Book that Never Was.’’ All the newspapers refused to publish the article.

[26] Abdulwahid Sykes, Ally Sykes, Dossa Aziz and John Rupia were the financiers of the movement from 1950 to 1961 when independence was achieved.

[27]See Andrew Bomani in Raia Mwema of 19 October 2012 ‘’Hamza Mwapachu na Nyerere Kuelekea Uhuru wa Tanganyika.’’ Hamza Mwapachu and Abdulwahid Sykes are the ones who recruited Nyerere into colonial politics in 1952 when Nyerere came to Dar es Salaam to work as a teacher at St. Francis College, Pugu. Hamza Mwapachu has been honoured in Kenya. Through efforts by Ali Mwakwere after learning that Mwapachu was a fellow Digo and that he was the first Digo to attend Makerere College in 1943 Mwakwere had a street in Kwale District his own home area named after Hamza Kibwana Mwapachu.

[28] Idd Faiz Mafongo was among the first 20 members who attended the first TANU meeting in August 1954. He was the Al Jamiatul Islamiyyya and TANU treasurer at the same time. As TANU treasurer he was responsible for collecting funds for Nyerere’s first trip to UNO in 1955.

[29]Mshume Kiyate a rich fish monger at Kariakoo Market and a strong member of TANU Elders Council adopted Nyerere as his own son in 1955. Mshume Kiyate was among TANU financiers. In 1964 when the army mutinied and Nyerere came back to power after the army was disarmed by the British TANU held a mass demonstration in support of Nyerere in which Nyerere gave a speech. Mshume Kiyate was the elder politician who was nominated by the party to go up the stage with Nyerere to cloth him with a traditional Swahili attire known as ‘’kitambi’’ as show of love, support and respect to him. Mshume Kiyate died a poor man failing even to pay his medical bills. His contribution to TANU and support to Nyerere remain unrecognised. Efforts to name Tandamti Street which he lived during the struggle after him has been resisted by City Council authorities.

[30] Kasella Bantu was the one who took Nyerere to Abdulwahid Sykes’s house to introduce them in 1952.

[31] G. Mutahaba, Portrait of a Nationalist: The Life of Ali Migeyo, East African Publishing House, 1969.

[32]Yusuf Ngozi was responsible for founding TANU in Kilimanjaro in 1955 despite of efforts by the colonial government to sabotage the party. History will remember Yusuf Ngozi for organising the Chagga to register as voters in the hated Tripartite Vote of 1958 which was known as ‘’Kura Tatu’’ in which an African was required to vote for a European, Asian and African candidate. Yusuf Ngozi died a poor man in 1989.

[33]Bilali Rehani Waikela one of the TANU founder members in Western Province in 1955 and Regional Secretary of the East African Muslim Welfare Society (EAMWS) was detained by Nyerere in 1964 for “mixing religion and politics.” His personal papers were of great help in understanding the EAMWS crisis of 1968 and the reasons why Nyerere detained prominent sheikhs and banned the society in 1968. A documentary of his political life has been made and although not officially recognized as a patriot, Muslims now consider him as one of the heroes of the independence movement. For more information see Mohamed Said, “In Praise of Ancestors,” Africa Events (London) March/April 1988.

[34]Sheikh Rashid Sembe (1912 – 1999) was among the TANU inner circle in Tanga who with Julius Nyerere plotted to circumvent TANU majority membership who where against contesting the Tripartite Election of 1958. This interesting story has never been made public. Other members to the Tanga Strategy were Amos Kissenge, Mwalimu Kihere and Hamisi Kheri. At the Tabora Conference of 1958 Nyerere was able to convince TANU to participate in the election. The outcome of this was resignation of Zuberi Mtemvu from TANU and formation of African National Congress (ANC) to oppose TANU and soon after a faction detached itself from TANU to form All Muslim National Union of Tanganyika (AMNUT). Nyerere referred to this story publicly only once in his lifetime and it was in passing. For details see M. Said ibid. The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes…pp. 233-252.

[35]Lameck Bogohe after many years of oblivion wrote an article (Nipashe7 Julai 2010) giving details of his contribution in the founding of TANU IN 1954.

[36]Titi Mohamed fell out with Nyerere soon after independence on issues concerning the role of Islam in free Tanganyika and was hounded out of TANU eventually charged in treason trial in 1970 with Oscar Kambona. She was given life sentence but was pardoned after serving few years in jail.

[37]Halima Selengia died in 2013 her contribution to the struggle for independence unrecognised.

[38]Issa Ziddy, Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir(1880-1979). Also See Mohamed Said, “Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir - The Moving Spirit of Muslim Emancipation in Tanganyika (1950 – 1968)” (Paper presented at Youth Camp Organised by Zanzibar University, World Assembly of Muslim Youth (WAMY) and Tanzania Muslim Students Association (TAMSA) 27th February – 4thMarch 2004. Sheikh Hassan bin Amir is credited for mounting support of Muslims to Nyerere by steering the party towards a path of nationalist-secularist ideology. Sheikh Hassan bin Amir fell out with Nyerere from 1962 and in 1968 was deported to Zanzibar as a prohibited immigrant. Sheikh Hassan bin Amir was a member of TAA Political Subcommittee in 1950 the inner circle which founded TANU in 1954. Other members of the TAA Political Subcommittee were: Abdulwahid Sykes, Hamza Mwapachu, Dr. Vedasto Kyaruzi, Steven Mhando, John Rupia and Said Chaurembo.

[39]On 27 th April, 1985, Julius Nyerere, before stepping down from power conferred a total of 3,979 medals to Tanzanians who had contributed to the development of the nation. None of those who took part in the struggle for independence was in that list.

[40] Kaggia, Bildad, Roots of Freedom 1921-1963: The Biography of Bildad Kaggia, East African Publishing House 1975. |

[41] At various times between 1945 and 1950 the African Association then known as Tanganyika African Association was led by the best brains in Tanganyika among them was the five doctors: Dr. Luciano Tsere, Dr. Joseph Mutahangarwa, Dr. Michael Lugazia, Dr W.E.B. Mwanjisi and Dr. Vedasto Kyaruzi. Others were Ali Juma Ponda, Hassan Suleiman, Ali Migeyo, Abdulwahid Sykes and Hamza Mwapachu to name a few.

[42] ‘An UnsungHero?’ Africa Events,London, November 1986 p.48.

[43] The editor of Africa Events was Mohamed Malamali Adam. Other contributors were Ahmed Saleh Yahya Ahmed Rajab and Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu.Africa Events magazine was considered a hostile paper to the government. In retaliation the government refused to approve transfer of its funds back to its main office in London. The government made a deal with the magazine that it would be allowed to circulate in Tanzania without molestation and will be allowed to repatriate its funds back to United Kingdom if it fulfils certain conditions. Africa Events obliged.

[45] V.M. Nazerali to Ally Sykes 12 th October, 1953 Sykes’ papers.

[46] In 1950s Abdulwahid’s office at Kariakoo Market where he was working as Market Master and Mwapachu’s office at Ilala Welfare Centre where he was working as Assistant Welfare Officer were the two centres of the robust African politics in Dar es Salaam.

[47] See Tanganyika Standard 19thJune 1953 TAA executive committee: Julius Nyerere, President; Abdulwahid Sykes, Vice-President; J.P. Kasella Bantu, General Secretary; Alexander M. Tobias and Waziri Dossa Aziz, Joint Minuting Secretary; John Rupia, Treasurer and Ally K. Sykes as Assistant Treasurer. Committee members were Dr Michael Lugazia, Hamisi Diwani, Tewa Said, Denis Phombeah, Z. James, Dome Okochi, C. Ongalo and Patrick Aoko.

[48] See ‘’Historia ya TANU 1954 – 1977,’’ Kivukoni Ideological College, Dar es Salaam 1981. In celebrating 50 years of independence in 2011 Abdulwahid and Ally Sykes the two brothers were honoured by President Kikwete as patriots who founded TANU and contributed in the struggle for independence.

[50] Chief David Kidaha Makwaia The Herald (Scotland) 12 May 2007.

[51]Hamza Mwapachu was at that time contributing articles to Fabian Society paper ‘’The Sentinel.’’

[52] For more information see ‘’Nationalism Breaking the Imperialist Chain at its Weakest Link,’’ in Tanzania Zamani Journal of the Historical Association of Tanzania Vol. III No. 2 1997, also see Tanganyika Political Intelligence Summary, March 1952, Sykes Papers.

[53] Artists in East Africa were recorded by Gallotone Records in South Africa and Jambo Records and Mzuri in Kenya.

[54] See Obituary by M. Said ‘’Singer Who Angered the Colonialists’’ ‘’The East African’’ in All Africa 7thJanuary 2008.

[55]The second song to be banned in Tanzania was a song by Sal Davis (Salim Abdallah) in which in praising the first government in Zanzibar the name of Prime Minister Mohamed Shamte was mentioned. After the overthrow of Shamte’s government in 1964 the song was banned.

[56]During the struggle Rashid Sisso came to be very close to Nyerere and Nyerere gave him the nickname ‘’Officer.’’

[57]Ramadhani Mashado Plantan came to Tanganyika from Mozambique as a child in 1905 he was among the children of Affande Plantan who came to Tanganyika with Sykes Mbuwane (father of Kleist Sykes) in 1894 as a leader of the Zulu mercenaries recruited by Hermine Von Wissman to help Germans in their war against Bushiri bin Harith in Pangani and Chief Mkwawa who were resisting Germany colonialism. The children of these Zulu mercenaries came to dominate local politics in Dar es Salaam. Schneider Abdillah Plantan was a powerful member of TANU and was secretary of Daawat Islamiyya (Muslim Call) under Sheikh Hassan bin Amir. His elder brother Mwalimu Thomas Plantan was president of the TAA who was overthrown by force by Abdulwahid Sykes and Hamza Mwapachu in 1950 paving way for radical changes in the association. Sheikh Hassan bin Amir was deported to Zanzibar following the crisis of the EAMWS in 1968 and Schneider Abdillah Plantan was detained.

[58] Catholics form 76% of all members of Parliament the remaining 24% seats are divided between Christians of other dominations and Muslims. Muslims control a mere 6% of the seats. Most areas which are under developed in Tanzania mainland are areas with Muslim majority like Kigoma, Tabora, Kilwa, Mtwara, Lindi etc. These areas are now re-examining themselves and are gradually turning into local factions of radical Muslim politics reminiscence of the era of nationalist politics of the 1950s. This could be a source of civil unrest in the very near future. Signs of this have begun to show in the recurrent violent conflicts between Muslims and the government. Tanzania has experienced the Buzuruga Muslim-Sungusungu Conflict (1983), Pork Riots (1993) and Mwembechai Upheaval (1998). For more information See Hamza Mustafa Njozi, Mwembechai Killings and Political Future of Tanzania, Globalink Communications Ottawa, 2000. (The book is banned by the government).

[59] The late Prof. Haroub Othman after reading Sheikh Ali Muhsin’s book Conflict and Harmony in Zanzibar 1997, and The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes 1924 -1968 The Untold Story of the Muslim Struggle Against British Colonialism in Tanganyika, Minerva Press, London 1998 and having come across hitherto unknown information on Nyerere was devastated because he was a great admirer of Nyerere as a patriot and a nationalist. The two books had painted him differently. Prof. Haroub confronted Nyerere and told him that the allegations in those two works have tarnished his image and he advised him to respond to them. Nyerere never did. Christian lecturers at Dar es Salaam University are discouraging students from making references to those two books. Dr. Harith Ghassany’s book Kwaheri Ukoloni Kwaheri Uhuru, has also come up with more information on Zanzibar Revolution hitherto unknown in Tanzania.

[60] In all historical references to Maji Maji War hero and Chief of Wangoni Ali Songea Mbano, his Muslim name “Ali” would be omitted and he would be referred to as Songea Mbano. Muslim names of Maji Maji fighters have been changed and Christian names inserted instead. The Maji Maji Museum at Mahenge in Songea has been desecrated removing all Muslim symbols in the exhibits completely wiping up a whole history of a people in a particular time setting of resistance to domination by a foreign power.

[61] Bilali Rehani Waikela one of the TANU founder members in Western Province in 1955 and Regional Secretary of the East African Muslim Welfare Society (EAMWS) was detained by Nyerere in 1964 for “mixing religion and politics.” His personal papers were of great help in understanding the EAMWS crisis of 1968 and the reasons why Nyerere detained prominent sheikhs banned the society in 1968.

[62] Maji Maji Museum in Songea which has been greatly desecrated removing all signs of Muslim symbols during the Maji Maji War with Germans. The Maji Maji Museum at Peramiho under the Catholic Church has closed its doors to young Muslims for fear of criticism for distorting history. All Muslim symbols in Maji Maji War against Germans have been obliterated in the Maji Maji Museum.

[63] A children’s book authored by the current writer, Torch on Kilimanjaro, Oxford University Press, Nairobi, 2007 has been blacklisted and cannot be included as a reader in schools because it contravenes the official history.

Dome Okochi Budohi a Luhya from Kenya was in Dar es Salaam during the struggle for indepedence in 1950s he is the holder of TANU card no. 6 given to him by Ally Sykes.

Dome Okochi Budohi a Luhya from Kenya was in Dar es Salaam during the struggle for indepedence in 1950s he is the holder of TANU card no. 6 given to him by Ally Sykes.

0 comments:

Post a Comment